Today is the Winter Solstice.

Depending on your view of things that means it’s either the shortest day or the longest night of the year.

The reality, of course, is that it is both.

And so it goes for other kinds of reality, too.

If you want to look for the struggles and problems around us, you’ll find them easily enough.

And…

If you choose instead to seek out strengths, virtues, accomplishments large and small, and acts of simple human kindness, I assure you, they are all around us as well.

For my part, I was born an optimist, and am most often drawn toward the daylight.

I recently had the opportunity to explain my worldview in a TedX event for the Nevins Library in Methuen, Massachusetts called “Making Connections.” I shared the stage with some tremendously talented speakers, including NECC’s own Adjunct Professor of Theatre and Communications Marisa Charest, and recordings of all our talks will be available soon on the TedX web site.

For now, on this Winter Solstice of 2022, in the spirit of light and hopefulness, here is “Why I Love Optimism”:

Why I Love Optimism

I have an important question for you:

What is this?

If you are a pessimistic sort of person, you probably know you are expected to say that it is a half-empty glass of water; and if you are an optimistic sort of person, you are expected to say that it is a half-filled glass of water.

Any physicists here today?

Well, if there were, they would likely point out that it is actually a completely full glass. It is, after all, filled with a combination of water and air, right?

Whatever your first impulse was to describe this, that’s OK. I’m not here to judge your worldview. I’m here to share with you why I see that glass not just as half-filled, but as completely filled and, in fact, actually overflowing with water, air, and…possibility.

I’m here to share with you why I love optimism.

For better or worse (personally, I’ve always found it to be better), I’ve been an optimist all my life.

Yes, that is me skydiving on my 40th birthday and giving the photographer a happy thumbs-up!

When I was younger, I was the editor of my high school newspaper. Recognizing all of the bad things the media, including our little school paper, usually reported on, I insisted on carving out a few inches of copy in each edition for what I called “The Optimist’s Corner,” and in that little space I reported on some of the goodthings happening on campus or around our community.

Later in life, I discovered there were more people like me, and I could actually join a civic organization called Optimists International. What, haven’t heard of them? True enough, there aren’t many chapters in New England, but there are more than 2,000 around the world, with hundreds of thousands of members all devoted to optimism and supporting youth in their communities.

More on that a little later.

Professionally, as a college leader and occasional consultant to all kinds of organizations, I work with optimistic tools like the Gallup Organization’s CliftonStrengths survey that helps people discover their strengths and talents, or Appreciative Inquiry, which is a way of asking questions with groups of people to tap into their successes and what gives them energy and inspiration.

Sometimes, people make fun of optimists like me.

This is a TedX for the Nevins Library, so it’s OK to get a little literary, right?

The French philosopher and writer Voltaire included an overly optimistic tutor named Dr. Pangloss in his 18thcentury novel Candide. No matter what happened in the story, from shipwrecks, to earthquakes and volcanoes erupting, to terrible diseases and more, Dr. Pangloss kept reassuring everyone that, “All is for the best in this, the best of all possible worlds.”

Pollyanna, the heroine of Eleanor Porter’s novel, learned from her father before she was orphaned how to play something they called “the glad game.” In every situation, no matter how grim, she could find something to be glad about. It began one Christmas when she was quite young and hoped to find a doll in the missionary charity barrel, but instead only found a pair of crutches. Her father made up the glad game by encouraging her to look on the bright side and be glad that she did not need to use the crutches.

Both Dr. Pangloss and Polyanna are so optimistic that to be called Panglossian or Pollyannish means that someone thinks you are unrealistic, perhaps even naïve or foolish, and that you don’t recognize the reality of a situation.

A.A. Milne gives us the choice of worldviews with two of our favorite characters from childhood, the always optimistic, if a little simple, Winnie the Pooh, and his dour, gloomy, unfailingly pessimistic companion, Eeyore.

If there’s a cloud in the sky, Eeyore will find it and worry about a thunderstorm, while Winnie the Pooh quickly discovers its silver lining.

But there is a lot more to this optimism thing than whether you are an Eeyore or a Winnie the Pooh, or whether you may be overly Panglossian or Pollyannish.

Back in 2005, Time Magazine published its first entire issue devoted to exploring “The Science of Happiness.” Stories delved into psychology, economic well-being, laughter clubs in India, and one article explained a study that found that between middle-aged men who consider themselves to be optimists or pessimists, the health and life expectancy benefits were the same as between men who were non-smokers and smokers.

We’ve known some of this for a long time.

We’ve known, for example, about the “placebo effect,” which is the body’s ability, under the right circumstances, to put mind over matter and heal itself through the power of willfulness. It is why many hospitals have “laugh carts” and why they made a movie about this guy—Patch Adams, who founded the Gesundheit! Institute to teach people about the healing effects of good humor.

In Greek Mythology, Pygmalion was a young sculptor who created a statue of a woman so beautiful he fell in love with it. The goddess of love, Aphrodite, took pity on Pygmalion and brought her to life for him.

From his experience, we get the “Pygmalion Effect,” which is a belief in someone so strong that it enables them to do things they might not otherwise have been able to do.

In the musical “My Fair Lady,” for example, Professor Henry Higgins turns what appears to be a loud, uncultured Cockney flower girl into a refined, polite society lady.

In my line of work, education, it can also make the difference between whether a student succeeds or not, because studies like “Pygmalion in the Classroom” have shown that the beliefs that we have about students often turn into self-fulfilling prophecies—for better or for worse.

Simply put, when teachers expect students to do well, they are more likely to do well; and when they expect students to do poorly, they are more likely to do poorly.

Our expectations often become our reality.

Are there any botanists in the room today?

Helios was the sun god in Greek mythology, who pulled the sun across the sky behind a winged chariot.

Just as a field of heliotropes, like sunflowers, bends and follows the sun as it moves across the sky, so, too, do we as individuals, or all of us as a group of people who work together for the same organization, or live together in the same community, or even more of us together as a nation of people, follow our collective vision toward the future.

When the vision calling to us is dark, dreary or even cataclysmic, then that is the vision we will be drawn toward.

When, instead, the vision we have for our future is compelling, something we strongly desire, and are inspired by, then that is the vision we will be drawn toward.

And, even if you don’t get everything you want, you’re more likely to get more of it than if you are living toward that darker version of your future.

Or, if you’re a sports fan, as the Great One Wayne Gretzky famously said, “You miss 100% of the shots you don’t take.”

Speaking of athletes, the best ones tend to practice positive visioning, because they know that, as important as it is to recognize and learn from your mistakes, it is absolutely essential not to be thinking about them all the time, because if you do, you’re going to keep making them.

Instead, whether you are a swimmer, a golfer, or a runner, in your mind’s eye, the best thing you can do is think about the perfect stroke, the perfect swing, or the perfect stride.

Because the brain doesn’t distinguish between what is real and what is imagined, when you imagine those perfect moves, the neural pathways in your brain react as if they are already happening, and over time, you can condition yourself to perform better.

I have a brother who lives in the Teton Mountains and is an expert skier. He can get dropped out of a helicopter anywhere on earth and ski his way out.

When he was teaching me how to ski in the glades, he gave me a very important piece of advice. What do suppose it was?

No, it wasn’t, “Don’t hit the trees.” If that is what you are thinking about, trees, then you are more likely to hit one.

His advice was, “Ski between the trees.”

It’s a simple but incredibly important mental shift. Instead of thinking about the trees, I think about the space between them, and that’s where I ski.

There is an entire strengths-based movement that has been underway in businesses and organizations for several years now.

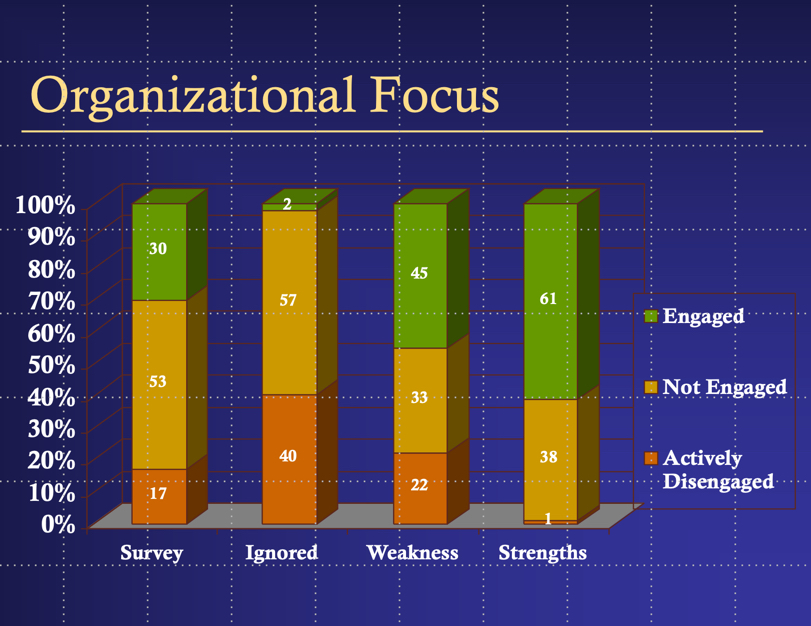

The Gallup Organization, which regularly surveys people all around the world about their attitudes, opinions, and experiences, has found that, on average, just over a third of people in a business or organization are “actively engaged,” or happy and doing their best, while just over half are “not engaged,” and nearly 20% are “actively disengaged,” which means they are really unhappy and probably spreading their unhappiness all over the place.

Interestingly, Gallup found that when bosses in organizations ignore people and don’t pay any attention to their strengths or their weaknesses, the numbers of employees “not engaged” and “actively disengaged” both go up dramatically.

When bosses focus on employee weaknesses, the percentage of “engaged” people goes up, but so does the percentage of “actively disengaged” people. After all, how much do you really want to keep hearing about the things you’re no good at?

Winning organizations, Gallup has found, have bosses who focus on people’s strengths. When they do this, the number of “actively engaged” employees soars to nearly two-thirds and the number of “actively disengaged” employees practically disappears.

So, these are just a few of the reasons I love optimism.

As an optimist, you can expect to have better physical health, less stress, more positive relationships, even a longer life!

The good news, according to Martin Seligman, the one-time president of the American Psychological Association and author of Learned Optimism and other books about happiness and a positive attitude, is that you can become an optimist if you want to.

This is one of my favorite pictures of my oldest daughter, Thomasina, when she was about twelve years old. She and some friends decided to try to waterski with a canoe. She was never going to make it up on those skis, but they had a lot of fun trying (and when the time came for her to get pulled behind an actual speed boat, she popped up on the first try!)

There are some very simple steps you can take and, like the positive visioning of an athlete, you can use them to train the neural pathways in your brain to follow them and make them normal habits over time.

At my house, every night at dinnertime we share our “Thankfuls and Hopefuls,” something we are thankful for and something we are hopeful for. You can easily do the same thing with your family, or by writing in a Gratitude Journal (they are easy to find in bookstores or online).

Lots of research points to the positive effects of expressing gratitude. It’s a modern-day version of Pollyanna’s “Glad Game.”

At work or in your community activities, know what you are really good at and play to your strengths as often as possible.

Recognize that you can’t control everything, but you can control your reactions. You can choose your attitude, and how you respond can go a long way toward turning a bad situation into a better one.

Sometimes, a problem or challenge just needs to be “reframed.” Instead of wallowing in what you don’t want, and therefore focusing even more on it, try to identify what you do want, or what you want more of, so you can focus on that instead.

For example, since this TedX Talk is happening at the Nevins Library, the American Library Association recently released its State of America’s Libraries report for 2022, and among some of the top challenges libraries are facing, they included “Disinformation” and “Book Censorship.”

Reframing those challenges might lead you to think about them as “Reliable Information” and “Open Access to Books.”

Reframing doesn’t get rid of challenges, but like skiing between the trees, it allows you the freedom of thinking about them in more positive, energy-giving ways, which can help you tap into creative solutions you may not have thought about if you were just focusing on the problem.

And, perhaps the simplest thing of all: smile.

Children smile an average of 400 times a day. Happy adults smile 40 or 50 times a day. Average adults only smile about 20 times a day.

When you smile, your brain releases tiny molecules called neuropeptides that actually fight stress. Other neurotransmitters like dopamine, serotonin and endorphins work as pain relievers, reduce blood pressure, and strengthen your endurance and your immune system.

Studies have shown that people who smile appear more likeable, courteous and competent. Smilers tend to be more productive at work and may even make more money.

And, all that smiling and all those positive results create more smiling and more positive results.

It’s a wonderful, optimistic cycle.

I mentioned earlier that I was involved with Optimist International, a worldwide volunteer organization that serves children and communities, and promotes optimism as a way of life.

I was the president of the Auburn Hills, Michigan chapter of Optimist International for a while. Each Thursday morning at 7:30 a.m. we would meet at our local Boys and Girls Club, say the Pledge of Allegiance, have breakfast, listen to a speaker, and plan our activities for the week.

We ended each meeting at 8:30 by reciting the “Optimist Creed,” originally published by Christian Larson in 1912, and no less aspirational and hopeful more than a century later.

It goes like this:

The Optimist Creed

Promise Yourself

To be so strong that nothing can disturb your peace of mind.

To talk health, happiness and prosperity to every person you meet.

To make all your friends feel that there is something in them.

To look at the sunny side of everything and make your optimism come true.

To think only of the best, to work only for the best, and to expect only the best.

To be just as enthusiastic about the success of others as you are about your own.

To forget the mistakes of the past and press on to the greater achievements of the future.

To wear a cheerful countenance at all times and give every living creature you meet a smile.

To give so much time to the improvement of yourself that you have no time to criticize others.

To be too large for worry, too noble for anger, too strong for fear, and too happy to permit the presence of trouble.

Thank you.