Frank Galati died this week.

He was 79 years old, and though he may not have been a household name for everyone, he had an enormous influence on me.

Galati was a professor at Northwestern University and a tremendously talented Chicago-area writer, director, and actor, long associated with the Windy City’s Goodman and Steppenwolf Theater companies, two of my favorites.

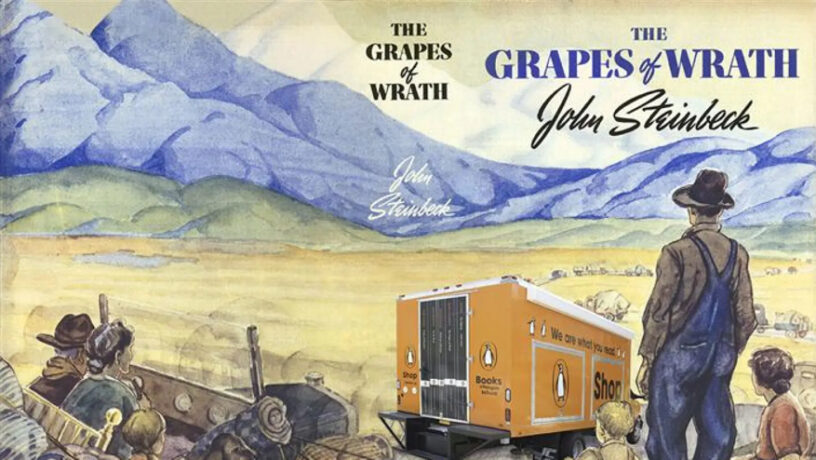

In 1990, when I was in grad school studying theater and aspiring to be like Frank, he convinced John Steinbeck’s widow to release the rights to The Grapes of Wrath, then wrote and directed an adaptation of the novel starring Gary Sinise that eventually launched from the Steppenwolf to Broadway, earning two Tony Awards, for Best Play and Best Direction of a Play.

In his review for the New York Times, Frank Rich wrote of the cast in Galati’s adaptation, “It is an ensemble that believes in what Steinbeck does: the power of brawny, visceral art, the importance of community, the existence of an indigenous American spirit that resides in inarticulate ordinary people, the spiritual resonance of American music and the heroism of the righteous outlaw.”

I was twenty-three years old, swimming in the works of Sam Shepard, David Mamet, and Lanford Wilson, when along came Galati and this powerhouse production. It was heady, awe-inspiring stuff.

Galati’s passing sent me to the back shelves of my library in search of Steinbeck’s novel about the Joads, an Oklahoma family, driven off their farm in the 1930s by the poverty and devastation of the Dust Bowl. Hearing about valleys of plenty and good jobs out west, they join the migration along the “Mother Road” to California, suffering the calamities and maltreatment of the millions of homeless Americans during the Great Depression.

Beyond capturing a terrible and traumatic decade of American history, The Grapes of Wrath is also a study in human nature, a sometimes searingly painful and sometimes gloriously uplifting examination of how people organize into communities, treat one another, and struggle to survive and to thrive.

The events of The Grapes of Wrath are nearly a century old now but thumbing through the pages of my dog-eared copy over the past few days, I was reminded of just how universal and timeless some of those themes still are today.

Migrants and the Fear of the “Other”

A migrant is simply a person moving from one place to another, especially to find work or better living conditions.

While The Grapes of Wrath tells the story of one migrant family from Oklahoma, the Joads, traveling and suffering westward to California to pick peaches and cotton and live in shanty towns, they are symbols of the hundreds of thousands of other migrants who made the journey.

Along the way, they are threatened, robbed, scorned, beaten, and taken advantage of in innumerable ways, mostly by their own countrymen who have come to view these “Okies” as outsiders and “Reds” arriving not to work honestly and build better lives for themselves but, in echoes of modern-day scaremongering, to take what doesn’t belong to them and to upset the order of things with labor unions and Communism.

As Steinbeck explains:

In the West there was panic when the migrants multiplied on the highways. Men of property were terrified for their property. Men who had never been hungry saw the eyes of the hungry. Men who had never wanted anything very much saw the flare of want in the eyes of the migrants. And the men of the towns and of the soft suburban country gathered to defend themselves; and they reassured themselves that they were good and the invaders bad, as a man must do before he fights. They said, These goddamned Okies are dirty and ignorant. They’re degenerate, sexual maniacs. These goddamned Okies are thieves. They’ll steal anything. They’ve got no sense of property rights. And the latter was true, for how can a man without property know the ache of ownership? And the defending people said, They bring disease, they’re filthy. We can’t have them in the schools. They’re strangers. How’d you like to have your sister go out with one of ’em? The local people whipped themselves into a mold of cruelty. Then they formed units, squads, and armed them—armed them with clubs, with gas, with guns. We own the country. We can’t let these Okies get out of hand. And the men who were armed did not own the land, but they thought they did. And the clerks who drilled at night owned nothing, and the little storekeepers possessed only a drawerful of debts. But even a debt is something, even a job is something. The clerk thought, I get fifteen dollars a week. S’pose a goddamn Okie would work for twelve? And the little storekeeper thought, How could I compete with a debtless man?

John steinbeck

A century later, America’s attitudes toward migrants are still, at best, ambivalent, and the rhetoric used to describe them is often unsettlingly similar to the curses hurled at the Okies in The Grapes of Wrath, with consequences that can be just as deadly.

This week, after a year in which U.S. border authorities reported more than two million illegal crossings by migrants, mostly from Central and South America, President Biden announced significant restrictions on people seeking refuge at our border with Mexico, a move that, despite precautions, is almost certain to create humanitarian crises to our south.

There are sound national security, public health, and economic reasons for countries like the United States to not simply have “open doors” at their borders, but it has been nearly thirty years since comprehensive immigration reform laws last made it through Congress, despite lawmakers and a general public on both ends of the political spectrum agreeing that our current system is broken.

Changing Gender Roles

Pa Joad, the family patriarch, is emblematic of most of the men in The Grapes of Wrath. He is a

taciturn, fiercely independent, hardworking laborer whose main purpose is to provide for his family. But the indignities he faces, from the loss of his farm in Oklahoma to unemployment and homelessness out west, drain the drive and spirit right out of him.

As Pa grasps for the way things used to be, Ma Joad takes over as the leader of the family, making decisions about when they will move on, where they will camp, and how they will interact with others they meet on the way.

When Pa laments his diminished role, and despairs that it “Seems like our life’s over an’ done,” Ma reassures him that, “Woman can change better’n a man…Woman got all her life in her arms. Man got it all in his head. Don’ you mind. Maybe— well, maybe nex’ year we can get a place.”

She explains, “Man, he lives in jerks—baby born an’ a man dies, an’ that’s a jerk—gets a farm an’ loses his farm, an’ that’s a jerk. Woman, it’s all one flow, like a stream, little eddies, little waterfalls, but the river, it goes right on. Woman looks at it like that. We ain’t gonna die out.

People is goin’ on—changin’ a little, maybe, but goin’ right on.”

A lot has been written recently about a similar male malaise and changing gender roles in America.

Young women are outperforming young men in the classroom from early childhood, when they are more likely to be “school ready” by age five, through college, where they outnumber men and earn far more degrees (here at NECC, nearly two-thirds of our students are women, and last year they earned 67% of our degrees awarded).

In the workplace, the “Great Resignation” has impacted men more than women, with the largest drop in employment among men aged 25 to 34; and men now account for three out of every four “deaths of despair” such as suicide and drug overdoses.

Economist Richard Reeves tackles some of these challenges in his recently published book, Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male Is Struggling, Why It Matters, and What to Do about It.

Reeves explores neuroscience and classroom dynamics that are, generally, better-suited to the brain development and learning styles of women; the rapidly changing nature of work in a knowledge-based economy; fatherhood and family dynamics and more.

Some of his recommendations include “redshirting” young boys to give them an extra year in the classroom when they are young, strengthening vocational education and training, and putting the same kind of emphasis on attracting men into “HEAL” (Health, Education, Administration, and Literacy) professions as we do into encouraging women into STEM fields.

Socioeconomic Opportunity

One of the most stirring moments in the original 1940 John Ford-directed movie of The Grapes of Wrath was when Tom Joad, played by a very young Henry Fonda, was saying goodbye to Ma Joad. He had killed a man who murdered his friend, Jim Casy, and was fleeing to protect the family and to join farm laborers in organizing against the injustices they were facing.

When a worried Ma Joad asks Tom how she will know about him and what happens to him, he reassures her:

I’ll be all around in the dark – I’ll be everywhere. Wherever you can look – wherever there’s a fight, so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever there’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there. I’ll be in the way guys yell when they’re mad. I’ll be in the way kids laugh when they’re hungry and they know supper’s ready, and when the people are eatin’ the stuff they raise and livin’ in the houses they build – I’ll be there, too.

john steinbeck

I’m happy to live in a state that, with equal enthusiasm and expectation, easily transitions from Governor Charlie Baker, a 6’-6” male Republican regularly named one of America’s most popular governors for most of his eight years in office, to Governor Maura Healey, a 5’-6” Democrat, Massachusetts’ first female governor and one of two lesbian governors in the country.

Tom’s speech about social justice reminded me of this week’s inaugural address by our new Governor Healey in which she pointed out the many socioeconomic inequities still facing residents of Massachusetts, but also stirringly encouraged us to remember that:

We share a legacy in this state. Our nation was born here, not with a whimper but with the spark of revolution. A hunger for something new and a demand for something better. We established the first public park and the first American public library. The first American lighthouse, railroad, and subway. The first basketball game.

Our state Constitution recognized our natural and essential rights and declared them to the world. The people of Massachusetts have always believed in protecting these rights, and dedicating them to a higher purpose. We were the first to guarantee that health care is universal, and, twenty years ago now, that love is, too. It is in that spirit of common humanity that I stand before you today, representing another historic first.

This state achieves its higher purpose when the bedrock of individual freedom meets the bond of the public spirit. This is our common wealth, in the truest sense — equally ours, equally yours, whether your Massachusetts story began in an older time or in our own time.

This is why people come to Massachusetts. To write their own story, to become their own first, to take up the common good.

Governor maura healey

Frank Rich ended his review of Galati’s Broadway production by noting that, “The Steppenwolf ‘Grapes of Wrath’ is true to Steinbeck because it leaves one feeling that the generosity of spirit that he saw in a brutal country is not so much lost as waiting once more to be found.”

In that spirit, this week, I mourn the passing of a giant of the American theater, even as I am tremendously grateful for his contributions not just to art and culture, but to a profound sense that, whatever challenges we as a nation may face, we will eventually overcome them.