The stories I share in Running the Campus are usually my own: mostly my perspectives on issues in higher education, sometimes personal reflections, and occasionally, still, tales about my daughters, “Big Sis T and Little Sis Z.”

Today, though, I am sharing someone else’s story, in his words, as only he can tell it.

This afternoon, I joined dozens of college colleagues at Celebrating Ourselves and Each Other, an event funded by the MDRT Foundation through NECC’s Center for Equity and Social Justice, aimed at “creating experiences that help foster respect and open-mindedness; the support for both building bridges and a sense of belonging between NECC and the community.”

Today’s luncheon and conversation were an opportunity, as we near the end of Pride Month, to hear the personal stories of some of our campus leaders and to consider the challenges being faced by LGBTQIA+ communities across the country right now, as well as the importance of “courageous allyship.”

This is the story that Dr. Paul Beaudin, NECC’s Provost, shared with us:

Silence Equals Death

I grew up in the 1960s and ‘70s, two miles from Plattsburgh Air Force Base where my dad worked, and which housed B52 bombers to be at the ready should the Soviet Union decide to attack the United States.

As a child, the nuns at my Catholic grammar school told us that Plattsburgh would be the first place that the Soviets would attack because of those B52 bombers.

So, in addition to the mandatory fire drills, sometime between the multiplication tables and the rosary, we practiced air raid drills for the impending nuclear attack. Upon the sound of the siren, we were taught to kneel in the school hallways pressed tightly against the cinder block walls and cover our eyes so that the nuclear bombs that would fall from Soviet planes would not burn our retinas.

I was eight years old.

It was a simpler time, or perhaps a time for the simple!

My fear in elementary school continued into high school at Mount Assumption Institute for Boys. The fear there had little to do with nuclear annihilation and more to do with the bullying I faced because I was a skinny gay kid, a math geek, with acne, who played the euphonium in the school band.

A euphonium, by the way, is a mini tuba, of sorts.

Try to formulate a picture of a 15-year-old me.

Compared to my experience in high school, the distant Soviets were less frightening.

College took me away from Plattsburgh and high school bullies. The B52 bombers were replaced by the other B52s, a group that became famous for songs such as The Love Shack to which I danced in the clubs in Westchester County and New York City and the fears of my youth began to subside.

In May 1981, though, a journalist by the name of Lawrence Mass, writing for the New York Native, became the first journalist in the world to write about the beginning of an epidemic in New York City which became known as the “gay plague” and eventually as AIDS.

Early in the epidemic, infections were largely reported among gay men and, based upon some irresponsible claims, among Haitians. And Lawrence Mass and Larry Kramer and four friends advocated for the sick and dying by founding Gay Men’s Health Crisis.

In New York City, Act-Up was formed. A group of concerned gay men and women, supported by allies, gathered in New York City’s East Village and held vigils and rallies to demand government action under a banner that read Silence Equals Death.

Diseases attributable to HIV infection claimed the lives of 40 million worldwide and nearly a million Americans. “AIDS babies” languished in hospitals and were considered victims. Gay men and IV drug users were not considered victims and were vilified by many who believed that it was the fault of their own actions that brought about their illness and death.

Two of my former housemates died, as well as other friends.

What many folks never realized is that the allies of gay men set up secret clinics in the basements of New York City churches where alternative treatments were administered to try to save lives with medicines brought into this country from France even as little was being done by our government.

In fact, it took President Ronald Reagan until 1985, four years later, before he ever spoke of AIDS publicly.

The AIDS quilt became a way to remember those who passed and eventually AZT was used in treatment as well as antiretroviral medications with some success and we became less fearful.

And, gradually, things got better and after years of being afraid, my fear dissipated as schools became more welcoming of children who were members of the community, and Heather Has Two Mommies sold 35,000 copies, and same-sex couples were able to adopt children, and Ellen “came out” on prime time, and RuPaul founded an empire, and parents embraced the needs of questioning children, and in 2004, Massachusetts became the first state to legalize same-sex marriage.

And Pride celebrations began to blossom.

And people began to have the right to be who God made them.

In 2010 “don’t ask, don’t tell” was repealed.

And because of the voices of allies, mourners, and advocates, death and struggle did not equal silence.

After years, I was no longer afraid. I dealt with abuse and every bullying incident, and every death of a friend, and every conversation with an accepting and loving ally made me more courageous.

I am not afraid, but I am more concerned in my sixties than I was in my forties and fifties.

I am more concerned not because the acne of my youth has been replaced by sagging jowls or that I now have three different pairs of glasses, but I am still concerned.

I am concerned….

because Heather Has Two Mommies is not allowed on library shelves in some places,

because in some states, diversity, equity, and inclusion is being stripped from the curriculum,

because in some cities, drag entertainers can now be arrested for performing on public streets,

because in some school districts, LGBT children no longer enjoy the safety and protection in school that was somewhat recently afforded them,

because who uses which restroom consumes the thoughts of millions of Americans,

because in a small Texas town, librarian Suzette Baker was fired last year for refusing to remove books from the shelves that dealt with the life experiences of LGBTQ people,

because in some areas, businesses are now being pressured to not recognize diversity and celebrate Pride month,

because two weeks ago just up the road in Concord, New Hampshire, Neo-Nazis converged on a downtown venue and disrupted a drag story hour for children who were celebrating Father’s Day with their dads.

More than anything, I am concerned that allies and members of the community may become afraid or exhausted from fighting or reticent to speak by those who deride them as being “woke.”

You know, I woke, from fear. I refuse to be afraid. I am happy to work at a place where I can speak my truth….and my truth today is this:

When Avram Finklestein of New York City and his friends coined the phrase Silence Equals Death in 1986, it was not applicable to just that moment in time.

It is a message appropriate for the Jews, homosexuals, and gypsies in 1940s Germany, Poland, and Hungary;

It is a message about the 20,000 lost boys of Sudan and of Matthew Shepherd, a boy from Laramie, Wyoming;

It is a message for the victims of the Rwandan and Armenian genocides, of the Irish and Ukrainian famines, and the victims of the war now taking place in Ukraine.

Silence Equals Death is an appropriate reminder of what happens to Black and Hispanic males on the streets of America’s largest cities, in the criminal justice system, and in our prisons.

Silence Equals Death is appropriate for the indigenous people in this country, whose life expectancy is nearly a decade less than for other racial or ethnic groups.

It is a message important to those school children and college students, (and their parents) whose campuses have become places of mass violence.

Silence Equals Death harkens back to our enslaving history, to the struggles of all peoples of color, of women, and of members of the LGBTQ family.

I dream of a day when we don’t need lawn signs to remind us that Black Lives Matter or You Are Welcome Here emblazoned on the signs now posted on lawns in North Andover with the rainbow flag.

Silence Equals Death is a message for all of us, especially for today. Thanks for listening, thanks for being an ally, and thanks for not being silent. Our lives and our freedoms depend upon it.

Epilogue: The Normal Heart

Paul’s powerful message moved many of us in the room to tears, and prompted me afterward to share this short epilogue with him:

My father was a career Marine. When I was young, we moved around a lot, and I grew up on or near military bases. By middle school, we had settled down in Oklahoma, which, with its strong Southern Baptist roots, is one of several states to claim itself as the “Buckle of the Bible Belt.”

Politics were not a major feature in my family, but values were, and my upbringing was decidedly conservative.

As I’ve written about in Running the Campus before, I graduated high school, enrolled at the local community college, and in my first year changed my major from Journalism to Theatre, enjoying the creativity, expressiveness, and what I immediately recognized as the potential to reach people, affect them, and, in an 18-year-old’s way of thinking that has never really left me, somehow make the world a better place.

As a young actor, I had the opportunity to audition for and perform in dozens of plays, and was always on the lookout for new, compelling material.

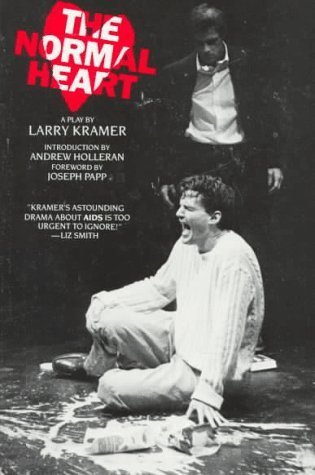

On a college field trip to the Bath House Cultural Center in Dallas, Texas in 1986 I saw The Normal Heart, a production that had a profound and lifelong impact on me, emotionally, artistically, professionally, and politically.

Larry Kramer, the founder of Gay Men’s Health Crisis Paul mentioned in his story, wrote The Normal Heartbased on events in his own life during the early years of the AIDS crisis in New York City.

The play is about Ned Weeks (based on Kramer himself), a reluctant but passionate and hard-driving activist trying desperately to draw public attention to the AIDS epidemic at a time when it was being largely ignored, to save the lives of gay men, and convince others that those lives are worth saving. In the process, Ned becomes estranged from his brother, loses his job and, eventually, his own lover, Felix, to AIDS.

The production drew on “agitprop” techniques of political theatre, with statistics about the number of deaths caused by AIDS, the paltry funding provided for seeking its cause and cure, and more painted on the walls of the set and the theatre itself; and its searingly powerful dialogue took aim at every person and institution that was staying silent in the face of the growing pandemic, including politicians, the media, the medical profession, heterosexist straight people and apathetic gay people.

Silence, The Normal Heart achingly portrayed, equals death.

Other plays and musicals about AIDS, like As Is, Angels in America, and Rent, followed, and each was revelatory and moving in its way, but The Normal Heart, for me, was an epiphany.

As much as any book, movie, play, or experience I had had in my young life until then, that production taught me the importance of questioning convention, of compassion, of not waiting until it is too late to speak up to right a wrong, and, as Paul offered so graciously in his story today, of allyship.

Thank you, Paul, for today’s essential reminder.