Note: This article appeared in the June 29, 2022 issue of Commonwealth Magazine

If you think it is hard to find workers for jobs today, just wait: It’s about to get a whole lot worse.

That’s the biggest takeaway from a research brief released last week by MassINC, “Sizing up Massachusetts’ Skilled Worker Shortage.”

The brief is a follow-up to a 2014 MassINC-UMass Donahue Institute study that estimated the number of working-age residents with four-year college degrees in Massachusetts would fall by 46,000 between 2020 and 2030.

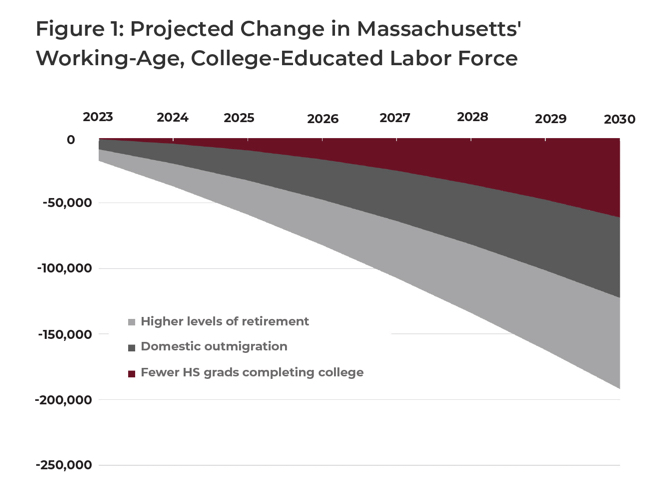

Thanks to rapidly changing demographic, socioeconomic, and educational trends, the alarming updated projection warns that the Commonwealth’s working-age, college-educated population may actually fall by as many as 192,000 residents, more than four times the original prediction, by 2030.

“Sizing Up Massachusetts’ Looming Skilled Worker Shortage.”

For an entrepreneurial, high-tech, highly-educated state with some of the best colleges and universities in the world that’s a long way to fall, and if it happens the landing is going to hurt—a lot.

Among the problems cited by MassINC:

Fewer High School Graduates Completing College

The birth rate across America has been declining drastically since the 2007 recession, particularly in the northeast, where, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Massachusetts has the second lowest birth rate in the entire country.

As a result, MassINC notes, “There will be around 250,000 fewer students moving through Massachusetts high schools between the class of 2020 and the class of 2030.”

On top of this, the newest generation is far more racially and ethnically diverse than the generations before it: nearly half of Gen Z is non-White.

Unfortunately, we have not made nearly enough progress in closing educational equity gaps in Massachusetts, because, as the brief points out, “Students of color are less than half as likely as White students to obtain a college degree.”

Consequently, the number of students enrolling in high school and eventually completing college degrees is expected to fall by around 30 percent by the end of the decade.

Higher Levels of Retirement

A demographic trend already underway got a big boost from the COVID-19 pandemic, as the number of college-educated adults retiring from the workforce in the 2020s is expected to be 30 percent larger than during the 2010s, which translates to a drop of about 87,000 highly educated and skilled workers between now and 2030.

Domestic Outmigration

While Massachusetts is indeed the most highly educated state in America (nearly half of the adults in the Commonwealth have a bachelor’s degree or higher), historically, many of those degree-holders migrated here from other states and other countries—and that is quickly changing.

As the MassINC brief reports, “Between 1990 and 2010, domestic and international migration combined for more than half of the state’s total increase in bachelor’s degrees. However, more recent data suggests the tides have turned. Since 2016, international migration has fallen steadily, and domestic migration has become a drain on Massachusetts’ population.”

Just before the pandemic, between 2016 and 2019, nearly 8,000 working-age, college-educated residents of Massachusetts moved away each year.

Five Ways to Avoid the Skilled Workforce Crisis

These problems are not new. We have seen them coming for quite some time, but have yet to take the steps needed to turn them around.

Nearly a decade ago, in 2014, the Massachusetts Department of Higher Education released “Degrees of Urgency: Why Massachusetts Needs More College Graduates Now,” which described a “perfect storm of factors,” including all of the ones cited by last week’s MassINC brief, that would lead to a shortfall of 65,000 degree-holders by 2025.

Degrees of Urgency pointed to a lack of investment in public higher education, the cost of college attendance, equity gaps for students of color, and workforce alignment as culprits in the looming crisis.

While efforts toward improvement are underway in each of these areas, we simply aren’t moving far enough fast enough to outpace the challenges that are running us down.

We need to think, and act, much bigger, and much more quickly.

Here are five steps we could take right away to avoid the impending skilled workforce crisis:

1. Significantly Scale Up Early College

By now, this one should be a no-brainer.

Piles of research from all around the country and from right here in Massachusetts demonstrate that Early College programs, partnerships that provide significant amounts of college courses and credits to students still in high school, ensure that more of those students, particularly low-income students and students of color, graduate from high school, go to college, and complete their degrees.

Given the significantly improved college graduation rates of Early College students, a tenfold increase in their number, from just over 4,000 a year today to more than 40,000 a year tomorrow, would increase the number of college-educated adults in Massachusetts by at least 60,000 residents by 2030.

As if those weren’t convincing enough reasons, a 2019 MassINC report, “Investing in Early College: Our Most Promising Pathway,” points to research showing a return of fifteen dollars for every public dollar invested in Early College programs.

The Massachusetts Alliance for Early College, which includes not only high school and college members, but leading business organizations like the Massachusetts Business Roundtable, the Massachusetts Business Alliance for Education, and the Worcester Regional Chamber of Commerce; and community and foundation leaders like the Boston Foundation, Smith Family Foundation, and Latinos for Education believes that “increasing access to Early College is key to promoting college and career success and closing equity gaps.”

Their goal is to make high-quality Early College programs available to every high school student in the Commonwealth, and we should do all we can through public policy and funding to make that happen.

2. Right-Size Credentials and Re-Align Postsecondary Certificates and Degrees

This one will require both employers and colleges and universities in Massachusetts to re-think how they work together: Far fewer jobs should require at least a bachelor’s degree, and many more need only an associate degree, short-term certificate, or some other kind of postsecondary credential.

A recent report from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, A Moment of Opportunity: The COVID-Era Job Market for Noncollege Workers, noted an important trend as the nationwide labor market is emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic: There have been far more “opportunity employment” job postings (jobs with a decent wage that do not require college degrees).

In fact, there was a 38% increase in these postings between 2020-2021.

This is a huge shift in the job market, after decades of “credential inflation” during which employers, especially in highly educated, tight labor markets, like here in Massachusetts, steadily increased minimum credentials for jobs from high school diplomas, to some college or an associate degree, to bachelor’s degrees, and beyond to graduate degrees, even when they did not really need those levels of education for the positions they were filling.

The job market is finally striking back.

That declining birth rate, a shrinking labor force, and the pandemic have all put more bargaining power into the hands of workers; and 68% of workers in America do not have a bachelor’s degree or higher (78% for Black Americans and 84% for Hispanic Americans).

Employers need workers, and they are ready to relax their requirements.

A few months ago, Governor Larry Hogan announced that the state of Maryland would be dropping the four-year college degree requirement for nearly half of the 38,000 jobs in their workforce, including positions in IT, customer service, and office administration.

The Business Roundtable is an association of chief executive officers of America’s leading companies (think Amazon, Best Buy, and Citibank—and those are just the ABC’s) “working to promote a thriving U.S. economy and expanded opportunity for all Americans through sound public policy.”

One of their newest initiatives is “a multi-year, targeted effort to reform companies’ hiring and talent management practices to emphasize the value of skills, rather than just degrees, and to improve equity, diversity and workplace culture.”

They aim to do this by rewriting job descriptions to include the skills the companies most need, then seeking, or developing, people with those skills through short-term credentialing programs like:

- Prior Learning Assessment

- Competency-Based Education

- Digital Badges

- Microcredentials

- Stackable Credentials

These are all new avenues of workforce alignment, curriculum development, and teaching and learning opportunities, and new ways to build greater equity into our credentialing processes.

They are also an opportunity for community colleges in Massachusetts, long overshadowed by the state’s better known and more prestigious private colleges and flagship university campuses, to shine.

In a recent article for American Compass, Harvard Professor Emeritus, founder of the Pathways to Prosperity Network, and Senior Advisor to the Harvard Project on Workforce Robert Schwartz pointed to each of these trends and noted, “At their best, community colleges are the most nimble, flexible, market-oriented institutions in our higher education system, working closely with employers to meet regional labor market demands.”

In June 2022, the Massachusetts Executive Office of Labor and Workforce Development reported there were 3,665,900 jobs in the Commonwealth. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Massachusetts leads the nation (except for Washington, D.C.) with the proportion of jobs requiring college degrees: Over 25%, or around 930,000, require a bachelor’s or master’s degree.

If we are able to “right-size” just fifteen percent of those jobs and align workers with newly created short-term certificate and associate degrees, we would be nearly 140,000 educated workers closer to closing our skilled workforce gap.

Massachusetts’ community colleges already collaborate with local employers, and now is an even greater opportunity for the state and employer partners to invest more time, money, and expertise in right-sizing and re-aligning the credentials needed for today’s workforce.

3. Invest in Student Support Services

As last week’s MassINC brief noted, “Students of color are less than half as likely as White students to obtain a college degree.”

Students of color are also far more likely to attend one of Massachusetts’ fifteen community colleges, which have significantly fewer resources to support them than other segments of higher education in the state.

That is why, working together, the Massachusetts Association of Community Colleges and the Department of Higher Education created the Supporting Urgent Community College Equity through Student Services (SUCCESS) Fund.

With $10.5M in support from the legislature last year, each of the state’s fifteen community colleges has developed or expanded student support services focused on improving educational outcomes with a focus on students of color and low-income students.

As a result:

- Statewide, the SUCCESS initiative served more than 4,000 students in 2021-22. Nearly half (48%) were low-income, more than half (54%) were first generation college students, and nearly two-thirds (62%) were Black or Hispanic.

- Significantly, 72% of SUCCESS students across the fifteen community college campuses were retained from the Fall 2021 to the Spring 2022 semester compared to 58% of the overall student population, an encouraging 14% improvement.

At a cost of just over $2,000 per student, the SUCCESS Fund is a modest investment in future workforce needs. The community colleges are looking to increase state investment in SUCCESS to $14M in FY23 and serve 7,000 students, with a long-term goal of $56M to improve educational attainment for at least thirty thousand Massachusetts residents.

The math on that investment, and the ROI to the Commonwealth and our future workforce, are pretty clear: for short money to support students better, we can help more of them graduate into higher-skilled, higher-wage jobs.

4. Invest in Adult Education and Training

Yes, nearly half of the adults in Massachusetts have a college degree; but that means that more than half do not.

In 2019, the National Student Clearinghouse produced “Some College, No Degree,” an analysis of more than 36 million Americans who had attended college since 1993 but left without completing a degree.

Just over half were women, and the average age was 42.

The same analysis determined that around ten percent of people with some college and no degree have a high potential to actually earn some kind of credential if they re-enroll.

At that time, pre-COVID, the Clearinghouse identified 636,107 adults in Massachusetts with some college and no degree. If just ten percent of those, around 64,000 could make it across the finish line, we would be making enormous progress toward avoiding our looming skilled workforce crisis.

How do we do that?

With over a million adults in the same situation, with some college and no degree, the state of Michigan created “Michigan Reconnect,” which offers free tuition to residents at least 25-years-old to earn an associate degree or Pell-eligible certificate at a community college.

Since the program’s launch in February of 2021, more than 90,000 Michiganders have been awarded scholarships for training, a higher-than-expected turnout that has driven the state’s initial investment from $30 million to $55 million, but Michigan Reconnect enjoys bipartisan support in the legislature, and early signs are already pointing to big gains in the state’s college-educated workforce.

A similar investment here in Massachusetts could pay enormous dividends not only in a more highly skilled workforce to meet the needs of Bay State employers, but in higher median family incomes and state tax revenues, reduced expenses for public services like subsidized healthcare, food and housing assistance, and more.

5. Roll Out the Welcome Mat for Immigrants

Massachusetts has been a beacon for international immigrants for centuries, including English pilgrims who arrived in Plymouth Harbor in 1620 to build the first colonies along the coast of New England.

Today, Massachusetts has the seventh largest population of foreign-born immigrants in the United States. One in every six Bay Staters is an immigrant, and one in every seven is a native-born U.S. citizen with at least one immigrant parent.

According to the American Immigration Council, twenty percent of the Massachusetts workforce are immigrants, and one in every five self-employed business owners is an immigrant.

Immigration has fueled Massachusetts’ standing as the leading higher education destination in the world, as well as our global success in healthcare, technology start-ups, and more.

But since peaking at nearly 50,000 new immigrants in 2017, immigration to Massachusetts has been falling, and the pandemic has only worsened the trend: Net immigration to the Bay State in 2021 was half what it was in 2020, and the lowest recorded in more than twenty years.

As a Boston Business Journal editorial recommended following the release of last year’s U.S. Census results, “If Massachusetts wants to hold onto its political power over the next decade, and companies want to continue to be able to tap local talent for the high-paying science and technology jobs that have fueled our economy over the past several decades, then rolling out the welcome mat for immigrants is the clearest way to do that.”

Here are three specific ways to roll out that welcome mat:

At the federal level, Massachusetts elected officials, as well as business, education and community leaders, should push Congress to bring some sanity and clarity to the H1-B Visa process (which allows employers to sponsor foreign workers for in-demand, high-skilled jobs); advocate for faster processing of the nation’s nine million green card holders eligible for citizenship; and create a clear path to citizenship for most of the eleven million undocumented immigrants living in the United States, especially the more than 800,000 young people registered through the DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) program.

Even as we aim for a rational, clear path to citizenship at the federal level, there are a number of ways to use state legislation to ensure Massachusetts encourages more immigration.

One part of the mission of the Massachusetts Immigrant and Refugee Advocacy Coalition (MIRA) is to “expand opportunities for all foreign-born people and their children, so they can make the most of their talent and labor.”

MIRA’s 2021-22 State Legislative Priorities include pending bills worthy of our support, like the “Safe Communities Act” that aims to “restore confidence in local institutions by ending the use of our public safety resources for federal immigration enforcement”; and the “Higher Ed Equity Act” that “Ensures that all MA high school graduates have access to in-state tuition at public colleges and universities, regardless of status.”

And lastly, there are thousands of immigrants already here in Massachusetts who have college degrees or other useful professional credentials from other countries but they cannot use them to apply for work until they are validated in the United States, a process that can be expensive, time-consuming, and bewildering, particularly if English language is a barrier, as it is for tens of thousands of immigrants in Massachusetts Gateway Cities.

Programs like PIES Latinos de NECC at Northern Essex Community College partner with the Center for Educational Documentation to bring the credential validating process into immigrant neighborhoods affordably, with translation services available.

Additional state and employer investment in English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) classes would also help relieve the waiting lists for these essential programs, which frequently run into the hundreds or even thousands of people in Massachusetts Gateway Cities.

Each of these five ideas requires substantial investment not only of money but of time, expertise, and partnering. But the potential result is over 300,000 appropriately educated workers—more than enough to cover the anticipated 192,000 worker shortfall predicted by the MassINC report.

Given the skilled workforce crisis we are facing, this is not a moment for incremental thinking and timid moves; it is a moment for bold ideas and even bolder action.