“This is certainly about the tragic death, assassination — political assassination of Charlie Kirk. But it is also much bigger than an attack on an individual. It is an attack on all of us. It is an attack on the American experiment. It is an attack on our ideals. This cuts to the very foundation of who we are, of who we have been and who we could be in better times.”

–Utah Governor Spencer Cox

NOTE: This article appeared in the September 30,. 2025 edition of CommonWealth Beacon Magazine.

When I was a teenage aspiring journalist in Oklahoma, working as a layout artist for minimum wage in the smoky, ink-fumed newsroom of the Midwest City Sun, I used the paper’s headline typesetting machine to print a small banner that hung over every desk I owned between 1984 and sometime in the early aughts: “I do not agree with what you have to say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.”

This valiant proclamation about the importance of free speech, attributed to the French philosopher and writer, Voltaire, seemed to embody everything that was essential and noble about my chosen profession, about democracy, and about our great nation.

Untested youthful idealism and bravado is easy.

Tacking a banner to the wall in 1984 was, I suppose, the equivalent of posting my personal creed to Instagram or X today, if even less impactful.

Living up to that idealism not just in word but in deed, through the tests of time as a writer, a professor, a father, an engaged citizen, and a college president has proven to be much harder, especially in today’s fiercely divided political landscape.

I have beliefs and strongly held opinions, and like anyone else, I am gratified when my perspective prevails.

Still, for the last four decades of my life and career, I have tried to keep Voltaire’s conviction in mind when faced with critical decisions about free expression on campus and in my community.

Because far more important than my perspective is the system of government and agreed upon set of cultural principles that allow me to have it and share it in the first place, and that allow others to do the same.

So, following the assassination of conservative activist and Turning Point USA founder Charlie Kirk on the campus of Utah Valley University earlier this week, I join leaders from across the political spectrum who have expressed condolences and offered words of warning about the rising tide of politically motivated violence in our country.

There are very few matters of public policy that Charlie Kirk and I would have agreed on, and I found some of his rhetoric, particularly about civil rights and the LGBTQ community, odious.

But how I feel about Kirk’s politics and personality in this moment is irrelevant.

Political disagreement should be settled at the ballot box or mediated through the legislative process, not forced by an assassin’s bullet.

We are at a moment when extremists on both the left and the right use strategies ranging from public shaming and cancelling, to censoring and intimidating not just to disagree with the opposition, but to silence them—sometimes permanently.

Freedom of Expression on College Campuses

A distressingly large proportion of college students across the country seem to agree with the tactics.

The recently released 2026 Free Speech Rankings from the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) find that a majority of college students (from nearly 70,000 surveyed at more than 250 colleges and universities) feel that controversial speakers should not be allowed on campus, and that it is acceptable to block other students from attending a campus speech.

Even more alarming, a third of the students surveyed find it acceptable, at least in some instances, to use violence to stop a campus speech.

That is wrong, and college leaders everywhere have a responsibility to turn this troubling trend around.

Encouragingly, at this fraught political crossroads, some are trying to do just that.

Last year, StoryCorps founder Dave Islay created One Small Step, an initiative designed to get people with different viewpoints talking to each other, and now he is bringing his mobile recording booth to college campuses in an effort to bridge political divides.

Braver Angels, an organization launched by Donald Trump supporters and Hilary Clinton supporters after the 2016 election with a mission to bring Americans together to bridge partisan divides now offers workshops and training to equip K-12 schools and colleges with the skills to navigate political differences.

Campus Compact, a network of more than 1,000 colleges and universities nationwide dedicated to effective community and civic engagement, offers tools like Better Discourse: A Guide for Bridging Campus Divides in Challenging Times.

And next month here in Massachusetts, the Department of Higher Education and Fitchburg State University are co-sponsoring “Civic Discourse in Action: Advancing Debate, Dialogue, and Deliberation in Massachusetts Higher Education,” a conference for faculty and staff to explore how they can help students build better capacity for principled debate and dialogue across differences.

The Four Freedoms

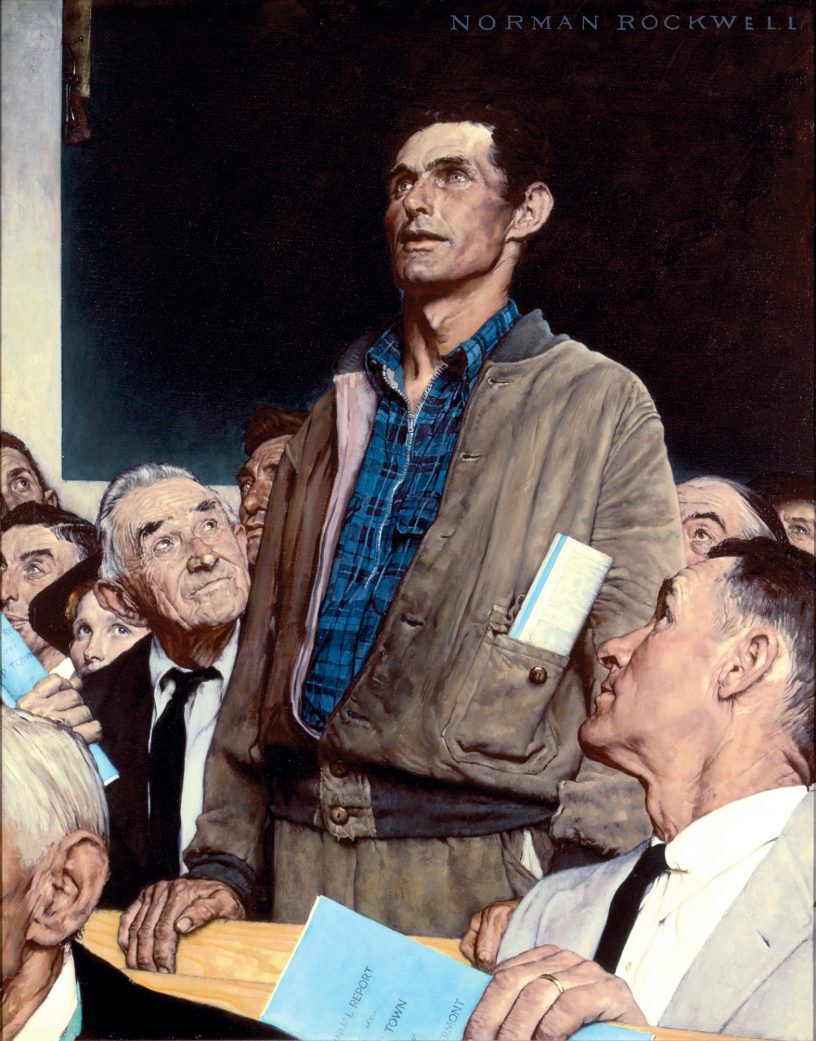

In 1943, halfway through its engagement in the Second World War, America’s best-known painter and illustrator, Norman Rockwell, delivered to his countrymen one of his most famous works: a series of paintings knows as The Four Freedoms.

Inspired by President Franklin Roosevelt’s “The Four Freedoms” State of the Union address to Congress, Rockwell’s paintings illustrate, in his signature Americana style, “Freedom from Fear”, “Freedom from Want”, “Freedom of Worship”, and “Freedom of Speech.”

Framed prints of “Freedom of Speech,” which depicts a Vermont farmer standing up to express his opinion at a town meeting, hang above my desk at home and on campus, as a reminder of this bedrock American value.

When the Four Freedoms were unveiled in 1943, the Saturday Evening Post commissioned four authors to write essays to accompany each illustration in the magazine.

Booth Tarkington wrote a fictional, cautionary parable inspired by Freedom of Speech which imagines a young Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini meeting in the Brenner Pass in 1912, where they plot to take over their countries by suppressing free speech and “purging” their enemies.

Over grapes, wine, and cheese, they lament nations like England and the United States where people create their own governments, listen to each other’s points of view, and vote their consciences, while conspiring to create societies where dissent is punished and the people live in fear.

“Speech is the expression of thought and will,” the youthful Hitler observes, “Therefore, freedom of speech means freedom of the people. If you prevent them from expressing their will in speech, you have them enchained, an absolute monarchy. Of course, nowadays he who chains the people is called a dictator.”

America’s destiny has always been to be a beacon for free thinking, free speaking, and free democracy; not a nation for dictators or for those, like Charlie Kirk’s assassin, who would suppress the freedom of the people.

And the campuses of America’s colleges and universities should reflect this openness to ideas and contrary views—places for free inquiry where we can choose not to agree with what others have to say, yet defend for all we are worth their right to say it.