Note: This article appeared in Commonwealth on April 24, 2021.

By Lane Glenn and Kevin Coppinger

The United States of America puts more of our citizens in jail than any other country on the planet.

While we have only 5% of the world’s total population, we have 25% of the world’s prisoner population. According to the World Prison Population List, an astonishing 716 of every 100,000 Americans are behind bars in local and county jails, state prisons, or federal penitentiaries.

To compound this challenge, imprisonment falls disproportionately on low-income and minority citizens. Though African Americans and Hispanics make up approximately 32% of the US

population, they are 56% of all incarcerated people in America.

While some kind of punishment is needed for an effective criminal justice system, the current approach to mass incarceration has proven too costly, and too ineffective, for everyone involved:

- The U.S. spends more than $80 billion each year on corrections, an amount that has increased at triple the rate of spending on Pre‐K‐12 public education over the past three decades.

- Recidivism — the rate at which those convicted of a crime and incarcerated commit another crime and return to prison — remains alarmingly high. A recent report from the U.S. Department of Justice indicates that more than 80% of state prisoners were arrested again at least once within nine years of their release.

- As the COVID-19 pandemic has clearly demonstrated over the past year, infectious diseases are highly concentrated in corrections facilities: 15% of jail inmates and 22% of prisoners — compared to 5% of the general population — report ever having tuberculosis, Hepatitis B and C, HIV/AIDS, or other sexually transmitted diseases. And, as the Marshall Project reported in December, by year’s end, one in five prisoners in the United States had contracted COVID-19, a rate four times as high as the general population.

- A criminal record can reduce the likelihood of a callback or job offer by nearly 50%; and this negative impact of a criminal record is twice as large for minority applicants.

With the passage of the Massachusetts Criminal Justice Reform Act in 2018 by the legislature and signed into law by Governor Baker, Massachusetts became the leader in a national effort to reduce rates of incarceration; including how juvenile offenders are treated in the criminal justice system, and how states can implement an array of services, such as education and employment counseling, behavioral therapy, substance abuse treatment, and domestic violence prevention to reduce the need for imprisonment.

As a result, according to an analysis by the Brennan Center for Justice, between 2007 and 2017, 34 states reduced both imprisonment and crime rates at the same time; and Massachusetts led the pack, with the steepest declines in both crime (40%) and incarceration (51%).

Massachusetts now has the lowest incarceration rate in the country.

Of all the ways proven to help reduce the likelihood that someone who has been in prison is going to commit another crime, the one that has the greatest impact for the lowest cost is quite clear: Education.

A national study of the effectiveness of correctional facility education programs by the Rand Corporation reveals that:

- Inmates who participate in correctional education programs are 43% less likely to re-offend than those who do not.

- The odds of finding a job after release for inmates who participate in correctional education is 13% higher than for those who do not.

- For every $1 spent on prison education, taxpayers save $5 on incarceration.

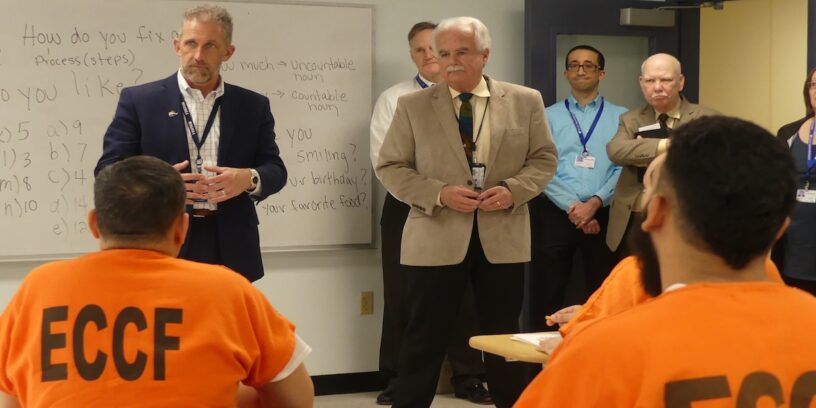

For all these reasons, the Essex County Sheriff’s Department and Northern Essex Community College are proud to be working together on a $1 million project to provide educational and vocational skills for inmates in the Essex County Correctional Facility, the Jail and House of Correction in Middleton, the Essex County Pre-Release and Re-entry Center in Lawrence, the Women in Transition facility, and the three Community Corrections Centers in Lawrence, Lynn, and Salisbury.

Even through the obstacles of the COVID-19 pandemic, NECC faculty and staff have been working “behind the walls” with corrections professionals at each of these facilities, providing inmates with the opportunity to complete their high school diplomas, learn English-as-a-second-language, improve reading, writing, and math skills, access a special lending library, and take classes in computer applications.

A generation ago, many people approached criminal justice with a “Lock them up and throw away the key” mentality. Today, whether it is more humane treatments for inmates with opioid addiction, mental health treatment services, or education and training, we understand that our role is not simply to punish, it is also to prepare our “residents” for living productive lives when they reenter society.

Our most important job, and the most important job of every inmate, every correctional officer, and every college teacher and counselor in this program is ensuring that when each resident’s time is served, they walk out the door better than when they entered, and are more prepared for a brighter future —and they don’t come back.

Dr. Lane A. Glenn is president of Northern Essex Community College, with campuses in Haverhill and Lawrence, and Kevin F. Coppinger is the Essex County Sheriff and former police chief of the City of Lynn.