I’m in Chicago this week for DREAM 2023, the annual conference for more than 300 community colleges across the country, including several here in Massachusetts, that are part of the Achieving the Dream network.

There is a lot you can say about us and our work, but the short version is: We are all vigorously devoted to knocking down barriers, to innovating and improving so that all of our students succeed and launch themselves into rewarding careers.

Today was a treat: Our keynote speaker was Raj Chetty, the Harvard economist and Macarthur Genius Fellowship award recipient who, as he puts it, “uses big data to study the science of economic opportunity: how we can give children from all backgrounds better chances of succeeding.”

I’ve been a fan of Chetty’s for years now. Here is a piece from the “Running the Campus” archives, updated for 2023 with some new material from his incredible Opportunity Insights project that demonstrates just how important community colleges are to American Dream notion that each generation is going to be more successful than the one before:

Community Colleges and the American Dream (Revisited)

A note to regular readers: This one is a bit wonky, with links to studies and surveys that you may want to take for yourself. Read it quickly on your phone if you like; or better yet, save it for your morning coffee or lunch break when you have half an hour or so to settle in and engage…

A century-and-a-half ago, just after America’s Civil War, Horatio Alger published Ragged Dick; or, a Street Life in New York with the Boot Blacks, the first of over a hundred “rags to riches” novels Alger wrote, assuring his countrymen that with the right attitude and work ethic, anyone could rise to the top.

The plot chronicles the life of a 14-year-old, immigrant, homeless boy, making his living shining shoes on the streets of New York City. Through hard labor, living virtuously and frugally, educating himself, and some lucky breaks, young “Ragged Dick” finds a career, amasses wealth, and becomes Richard Hunter, Esquire, a respectable member of the middle class.

Alger’s entire six-volume Ragged Dick series may well be summed up in six words in the first story, when young Richard advises Jimmy Nolan, a fellow bootblack who is not as ambitious and industrious as he is that, “You can if you want to.”

I’ve always felt that way myself.

I’m a strong believer in self-sufficiency; a dedicated (my family would say stubborn) do-it-yourselfer, from landscaping, carpentry, plumbing, and electrical work, to gardening, car maintenance, and, especially, cooking.

Academically and professionally, I’ve always been just as curious and driven to learn for myself and do the best I possibly can. It has always seemed to me that setting goals, working hard, and persevering through challenges will get you where you want to go.

That, after all, is the American Dream.

And for quite some time, that dream felt tantalizingly within reach for many Americans—a strong part of our national identity. We’ve had our ups and downs, sure, but in the decades following World War II, educational attainment, incomes, jobs with healthcare and pension benefits, and automobile and home ownership all climbed steadily.

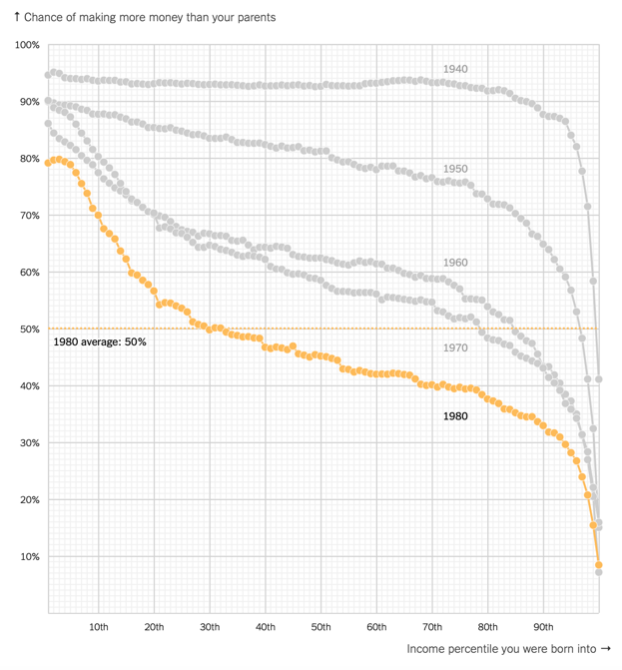

If you were born in 1940, as my father was, then you had a 92% chance of making more money than your parents.

The American Middle Class, particularly the Baby Boomer generation, grew to be one of the largest and most prosperous in the world.

But as tempting as that vision may have been, the game of life in the United States has never been played on a level field. We also have a history of bigotry, racism, misguided social and economic policies, and deeply embedded structural inequities that have always made it harder for those who start much farther behind to ever reach the finish line.

Like it or not, in America it has always been easier for a white, European, heterosexual male, born in the suburbs to an intact, college-educated family to make it into that middle class (or stay there) than it is for anyone else.

If you are female, a person of color, homosexual (or anything other than cisgender), a child of divorced parents, less educated, disabled in any way, or, especially, poor, you are less likely to move up the socioeconomic ladder.

It’s not impossible—just a whole lot harder, even if, as Ragged Dick suggests, “you want to.”

Not sure you believe me? See for yourself.

A few years ago, the Ford Foundation created “Your American Dream Score,” a survey designed to reveal factors that help you out or set you back in life, and spark conversations about opportunity and inequality in American life.

Click here to take the short survey. (Go ahead, it will only take a few minutes—I’ll wait.)

All set? Great.

I scored a 56, how about you?

According to the Ford Foundation, my score means “You’ve had much more working for you than against, with a few obstacles that you’ve had to overcome.”

On the obstacles side of the ledger, I suppose: I was born to young, unwed parents, who gave me up for adoption. I lived for a short while with a foster family, then was adopted by a career Marine and his wife with high school educations. Mom was in poor health and had a debilitating stroke while I was young, followed by years of ailments, including a brain tumor, breast cancer, and multiple heart attacks.

Early on, we moved around a lot, and I attended several different schools. I’ve always worked, sometimes at multiple jobs, and the economy wasn’t so hot when I began my professional career.

But the things working for me, it seems, helped outweigh those challenges.

I’m white, and a man.

My adoptive parents were high school sweethearts who stayed married for 56 years, and provided a loving home for me and my sister, until mom passed away (tough as nails, and still insisting she was the luckiest, happiest woman on Earth).

I grew up in relatively safe neighborhoods, with access to reasonably good public schools, developed a strong social network, stayed healthy, and found my way to college (with help from a modest scholarship from a local bank).

And, like Ragged Dick, I worked hard and caught a few lucky breaks.

Maybe even luckier than I knew, because according to Raj Chetty and his team of researchers on the Opportunity Insights, if you were born in 1970 (just a few years after me), your odds of making more money than your parents had plummeted from the near certainty of my father’s generation to only 62%.

And since then, I’m sorry to say, if you are a millennial it has fallen to 50/50.

So, what’s behind these generational challenges? The American Dream Score site explains some of the factors that may be helping, or hurting, you along the way. For example:

- Project Implicit project.

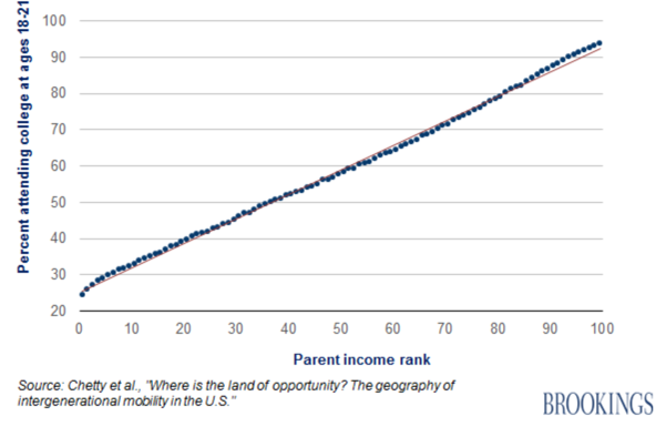

And then there’s this one: Your parents’ income which, as it turns out, may be one of the strongest predictors of whether or not you attended, and completed, a college education.

As the chart below indicates, there is basically a one-to-one correlation between income percentile and the odds a child will attend college, with children from the lowest income families having practically no chance at higher education, while top earning families are almost 100% likely to send their children to campus.

Harvard social scientist and author of one my favorite books on civic engagement, Bowling Alone, Robert Putnam, recently published Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis, in which he exhaustively details many of the reasons for the widening “opportunity gap” we are experiencing today.

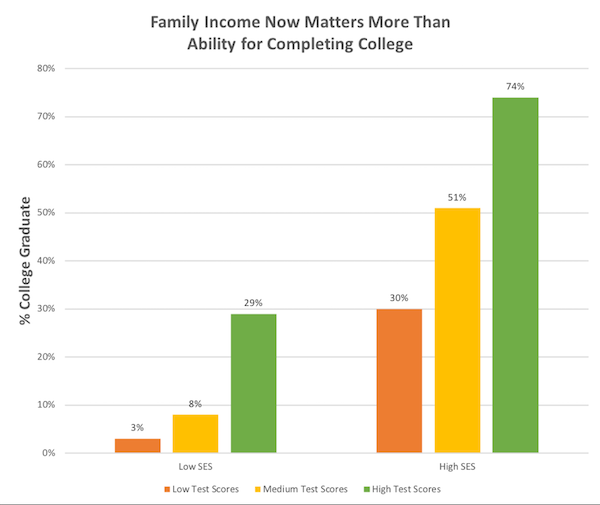

One of his startling, though not entirely surprising, findings is that family income now matters more than ability for completing college.

Or, as Putnam himself succinctly puts it: “Smart poor kids are less likely to graduate from college now than dumb rich kids.”

A bit harsh, maybe, but Putnam’s point is that it is often not the schools themselves that make the difference, but your “American Dream Score,” and the disadvantages or advantages you had growing up.

As the chart below, drawn from Putnam’s research, illustrates, on average, 74% of high socioeconomic status (“rich”) kids with high test scores complete college; while only 29% of low socioeconomic status (“poor”) kids with equally high test scores earn degrees.

Who are these kids from the low SES, and what happens along the way?

At community colleges like NECC, we can tell you, because we serve more of them than any other segment of higher education in America.

Most of our students are the first in their families to attend college. Two-thirds are low income, and can only attend classes part-time while working thirty or more hours a week. Over half are students of color, mostly Hispanic, many first- or second-generation immigrants and non-native English speakers.

Add to these challenges the number of NECC students with physical or learning disabilities, veterans or adults returning to school after years in the workforce, and young people raising children of their own, and it is not surprising that many take a long time to complete their degrees, or perhaps do not graduate at all.

But while area colleges like Tufts, BC, and Harvard with some of the best reputations (and the biggest price tags) in the world can boast near perfect graduation rates and alumni with soaringly high salaries, did those institutions actually help their graduates reach the pinnacle of success, or, as Putnam argues, would they have landed there anyway?

According to the Opportunity Insights project, some of the best colleges in the world seem to have very little impact on whether their students climb the socioeconomic ladder, mostly because they are already a rung or two from the top; while colleges like NECC are far better at serving disadvantaged students and helping them reach upward mobility.

In this online article from the New York Times, you can search for and see the profile of every college and university in America—the kind of students it serves, and how successful they are at helping lower income students reach the middle class.

Try it out for your alma mater, or click here to see the profile for Northern Essex Community College, and here are some of the things you will learn about us:

- The median family income for our students is $52,900, among the lowest in Massachusetts.

- About 18% of our students are from the bottom 20% income percentile, among the highest proportion in the state.

- After their education, 20% of our students move up two or more income percentiles, one of the best improvement rates in the Commonwealth.

In fact, out of 76 colleges and universities in Massachusetts, NECC is 14th, and third among community colleges, at helping students pursue the American Dream, and find careers, incomes, and lives for themselves better than where they started.

Tufts, BC, and Harvard? They lag way behind in 64th, 70th, and 71st place. Only about 11% of their students manage to move up two or more rungs on the socioeconomic income ladder.

There are some distressing takeaways from the data in the Equality of Opportunity Project. For example, even as the rich have been getting richer and the poor even poorer in America over the last couple of decades, higher education seems to be contributing to the divide: Elite colleges still admit the same small proportion of lower income students they did a generation ago, even as financial support for public colleges like NECC has drastically shrunk and we have less to spend on the neediest and most at-risk students on American college campuses.

But the hopeful news is that community colleges across Massachusetts and around the country continue to take what resources we do have and accomplish some amazing things with them, turning more “rags to riches” and helping to accomplish more American Dreams than any other segment of higher education today.