My mother and father were childhood sweethearts in Warren, Ohio who married in 1958, just after graduating from high school.

Dad had already enlisted in the Marines, and after the ceremony and the celebration, the newlyweds headed south to Camp Lejeune.

The motto of the United States Marine Corps is “Semper Fidelis” which means “always faithful,” and there is no better way to describe my father.

For the few and the proud, the Marines, “Semper Fi” embodies the Corps’ values of honor, courage, and commitment.

Faithful to his country, Dad spent more than twenty years in military service, including two tours of Vietnam.

During one of those tours, Dad took up running and earned the Navy Commendation Medal, in part by recruiting a bunch of fellow leathernecks to run with him, build morale, and turn around a struggling but crucial aircraft supply squadron.

Back home again years later, with the discipline and perseverance of a long-distance runner, Dad would rise by 4:00 a.m. each day, pound the streets for ten or fifteen miles, ride his bike to work, come home for his vegetarian dinner, and go to bed by 8:00 to get up and do it all over again.

In 1982 he ran the Boston Marathon in three hours (and added the blue t-shirt with the Mercury-winged sneaker on it to his collection of dozens of race jerseys).

Faithful to his wife and family, he lived steadfastly by Mom’s side for fifty-six years, until she passed away in 2014.

And many of those were not easy years. Mom had a stroke when she was 44 that left her partly paralyzed. Later, she suffered heart attacks, brain and breast cancer, and a number of other ailments that kept her mostly homebound.

Through it all, though, Mom smiled and waved away worry, and Dad did whatever needed to be done, including giving up running, to care for her.

When Mom died, I encouraged Dad to move north so he could be near family; but he felt closest to Mom in the house they had shared just outside of Houston, Texas. And besides, he said, New England winters are too long and too cold.

So, there he stayed, alone with his remembrances.

And time went by.

Then, one day he was in the produce aisle at the grocery store and couldn’t recognize the celery.

It was a moment that he had long feared, since losing his own mother, slowly and one painful lost memory after another until there were none left, to Alzheimer’s Disease.

In the frightening weeks that followed, more words began to escape him, and everyday tasks like cooking meals or cleaning the house became more difficult as he struggled to remember how to use the stove and where he kept the paper towels.

When the streets in the neighborhood where he had lived for twenty years became confusing to him, and he could no longer easily find his way home, he knew the time had come to stop driving, buy a winter coat, and head north.

Dad had always been a capable, healthy, upbeat, and self-reliant man, who was proud that he had never spent a night in the hospital in his life, and rarely visited a doctor.

But that was the first order of business when he arrived in Massachusetts in 2018 and moved in with me and my family. A couple of office visits and a few tests later, and we learned that it was not Alzheimer’s, but the early stages of Parkinson’s Disease Dad was experiencing.

We also learned that his particular condition is associated with Marines who were stationed at Camp Lejeune, where for decades the water was contaminated with industrial chemicals; and with Marines who had “boots on the ground” in Vietnam, where they were exposed to Agent Orange, the chemical used to eliminate forest cover and crops for North Vietnamese troops.

While still a serious diagnosis that required lots of care, Dad was relieved and even lighthearted when he heard the news. It meant that, although he was likely to begin to feel more physical effects of his condition, his memory lapses and moments of confusion may not tumble into the darkness of complete dementia.

And he was right—for a while.

With new medication, Dad’s physical and mental symptoms were more manageable, and he continued to stay with us. But we were at work or school all day while he was alone, and eventually we all recognized Dad needed more care—and company—than we could provide.

In February of 2020, on President’s Day, he moved into a small, comfortable assisted living facility just a few miles from our home.

Most of the two dozen or so residents there were older than Dad and not nearly as physically active. For years he ran marathons, and even with slight tremors and stiffening legs, he still managed to walk a few miles each day or ride an indoor exercise bike when the weather was cold.

Still, he made a couple of friends: a former Navy sailor with a bawdy sense of humor who always wore an “Uncle Buck” ball cap, and a kind, constantly smiling retired schoolteacher a few years younger than Dad, who would take morning strolls along the nearby streets with him.

Then, suddenly the whole world changed.

In mid-March his home, like others across the country, went into lockdown, carefully restricting visitors, feeding residents alone in their rooms, and requiring staff to wear masks and other protective equipment.

It was the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the two years that followed were a confusing and often frightening time, especially for seniors like Dad, living in nursing homes.

Those two years also had their happy moments for him. That constantly smiling schoolteacher, it turned out, had Dad smitten, and by the time we celebrated his 80th birthday in the summer of 2020 (in the open air of the backyard, with only a handful of healthy, masked guests) the two of them were like giddy teenagers, holding hands and beaming (cue Joshua Kadison’s ode to elderly puppy love, “Painted Desert Serenade.”)

Despite his new puzzle room crush, though, he had not forgotten Mom.

Pictures of the two of them hung proudly and poignantly around his room.

A pair of black and whites from high school graduation and their wedding, more than half a century ago.

A Marine Corps Ball sometime in the early ‘70s, with Mom’s fiery red hair ablaze over a green gown—her favorite color—and Dad looking sharp in his dress blues and gleaming white hat.

And there in the center of it all, a hand-carved, wooden Marine Corps insignia, mounted on a field of maroon, surrounded by Dad’s stripes and bars, with the proud motto unfurling along a banner in the eagle’s beak: Semper Fidelis.

Always faithful.

Among the countless diseases that afflict humankind, those that steal away the mind are some of the most insidious.

With his Parkinson’s-related dementia, Dad’s memory deteriorated, outpaced even further by his new friend’s Alzheimer’s disease.

By the spring of last year, they did not recognize each other, or anyone else, and Dad was moved to a nearby nursing home (cue Zach Bryan’s poignant ballad of love turning to loss in storm-tossed memory, “Billy Stay.”)

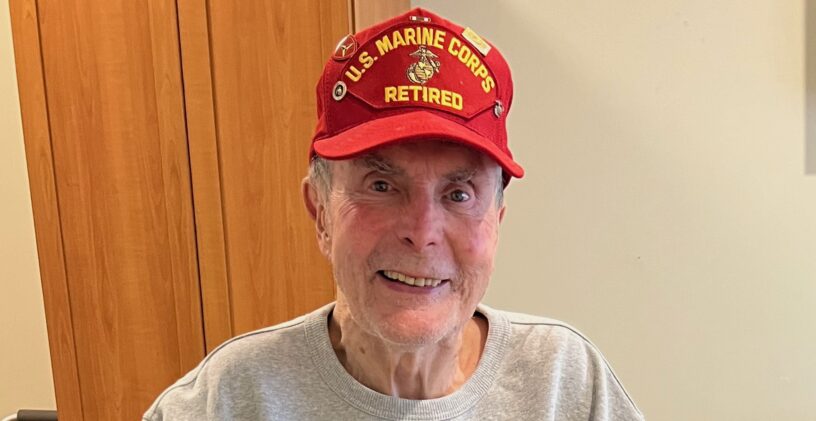

Since then, the man I remember mostly as the 6’-1” fleet-on-his-feet lean Marine had been wheelchair-bound, the disease claiming most of his memory, except for fragments of his childhood and his military service.

When I visited him, we would listen to old radio shows like The Lone Ranger and The Shadow, which he first heard when he was ten years old, and look through photo albums at pictures of a young, square-jawed, crew-cut Marine, who led by instinct and his own core principles.

Dad was the most disciplined and dutiful man I’ve ever known. He always did what he said he would do, and when he committed to something, he went all the way.

Just ask any of the Marines who served with him.

Or Mom.

I was at his side holding his hand as he passed away peacefully yesterday afternoon.

The hospice nurse, who came to know Dad pretty well while caring for him, and whose own father had served in the Marines, said, “They just don’t make men like him anymore.”

He certainly set the bar high.

May we all strive to reach it.

Semper fi, Dad.