“History is written by the victors, but it’s victims who write the memoirs.”

Carol tavris

“Those who cannot remember the past are doomed to repeat it.”

george santayana

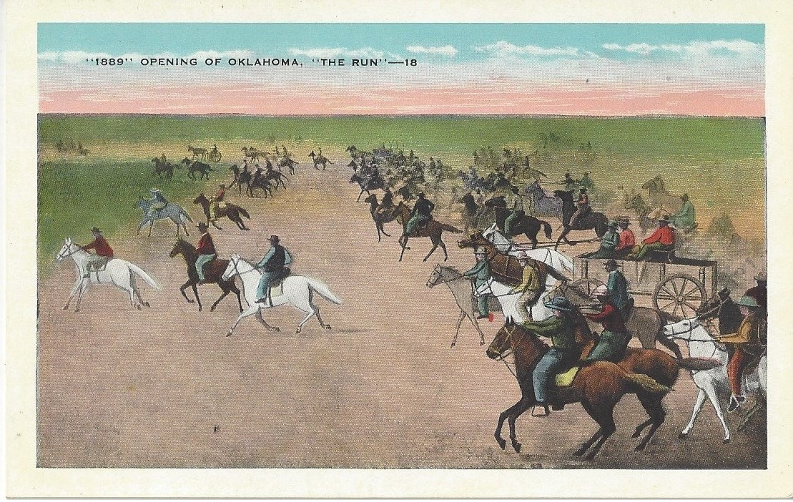

On April 22, 1889, more than 50,000 ambitious settlers lined the borders of the “Unassigned Lands” in what is now central Oklahoma. At exactly 12:00 noon with the sun high up in the sky overhead, bugles blared, cannons thundered, shotguns blasted, and throngs of “Boomers” raced on horses, wagons, trains and even bicycles to stake their claims (along with the “Sooners” who snuck in early) to a piece of nearly two million acres in one of the largest “land runs” in history.

Was it a momentous day for American Manifest Destiny, a victory of rugged individualism and the indomitable pioneer spirit over the untamed wilderness, an enormous transfer of wealth and an opportunity for everyone, including women and African Americans, to become landowners?

Or just another treaty-breaking, land-grabbing swindle by a colonizing federal government that had already nearly eradicated many Native American tribes and forced survivors onto inhospitable parcels of “Indian Territory?”

It depends on who you ask.

When I was a kid, growing up in Oklahoma, we learned how we carved statehood out of the Wild West through ingenuity and perseverance. As recently as 2020, the state’s official web site proudly declared:

This is a place that was built from scratch, made by people who gave up everything to come here from all over the world to create something for themselves and their families…We started this place with a land run in 1889 — and honestly, we’re still running, still making, still pioneering.

There was a strong sense of pride in this origin story of ours.

Third- and fourth-graders in Oklahoma public schools used to participate in “Land Run Reenactments” every year on April 22nd, scampering across playgrounds to be the first to lay claim to the “unassigned” property out beyond the sandbox.

The fight song for the University of Oklahoma is “Boomer Sooner,” and the school mascot, one of the most recognizable and popular in all of college sports, is the “Sooner Schooner,” a replica of the Conestoga wagons used by 19th century western settlers, drawn onto the field by a pair of white ponies named “Boomer” and “Sooner.”

Of course, that origin story overlooks a lot, beginning with the people who were there long before the Boomers and the Sooners.

The southern plains of America have been inhabited for thousands of years, at least since the end of the last ice age.

In modern history, between 800-1500 CE, the Mississippians, the Wichita, Caddo, and Tonkawa People lived there; then came the Plains Apache in the 1600s, followed by the Comanche, Kiowa, Osage, and Quapaw in the 1700s.

In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, and forcibly relocated thousands of Native Americans from their lands in the southeast to the still sparsely populated “Indian Territory” in the southern plains of present-day Oklahoma. Members of the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw and Seminole tribes were marched, in the middle of winter in brutal conditions, from Florida, Georgia, Tennessee and Mississippi along the “Trail of Tears,” where thousands died of starvation, disease, and exposure.

They were told that they could make new lives for themselves, away from constant conflicts with the growing White population, on lands they would own forever. But as new treaties were negotiated, the Civil War split tribal alliances, and Westward Expansion continued insatiably, the tribes found themselves on shrinking reservation lands, once again battling for survival.

The land runs of the late 19th century that gave “Unassigned Lands” to new settlers took those lands from Native Americans.

All this is the history I learned later, in 1987, when I moved to the capital of the Cherokee Nation in Tahlequah, Oklahoma to be an actor in the Trail of Tears drama at the Tsa-La-Gi outdoor amphitheater, and a college student at Northeastern State University.

For three summers I played John Ross, the (mostly Scottish) Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, who led his people for nearly forty years, through one of the most tumultuous periods in their history. Along with an enormous cast of mostly Cherokee actors and dancers, I reenacted that history for busloads of tourists from across the country and around the world in a giant outdoor theatre, five nights a week between Memorial Day and Labor Day.

During the years I spent in Tahlequah, I learned, and lived, new perspectives on the history I thought I knew so well. In addition to the theatre, the Cherokee National Historical Society operated a beautiful museum, art gallery, and replicas of village life from different periods in Cherokee history.

Surrounded by the artists at Tsa-La-Gi, I saw firsthand the pride in the tribe’s history, culture, and heroes; as well as the socioeconomic, educational, and healthcare challenges compounded by generations growing up on the reservation.

I haven’t seen much of Oklahoma since leaving it in 1991, but last week, on a rare return trip with Little Sis Z to visit family, do some sightseeing, and stop by the Ponca Tribal Pow Wow, that history came rushing back to me.

We spent one night of our visit in downtown Oklahoma City’s Bricktown district, where sculptor Paul Moore’s Centennial Land Run Monument, completed in 2019, sprawls along a canal, commemorating that fateful day in April of 1889.

With 47 bronze statues, each one-and-a-half times life-size, stretching nearly 400 feet, it is one of the largest series of sculptures anywhere in the world.

Is it an amazing celebration of pioneer spirit, rugged individualism, and the founding of America’s 46th “Sooner State,” Oklahoma?

Or is it an appalling glorification of greed, theft, brutality and colonial domination taken to the brink of cultural extinction?

It depends on who you ask.

A commemorative stone marker on the site proudly declares, “The Oklahoma Centennial Land Run Monument pays tribute to the courageous settlers who on April 22, 1889 helped shape Oklahoma’s unique history. It also recognizes present day pioneers who through their untiring dedication to this project have immortalized a defining moment in our state’s epic creation.”

Paul Moore, the monument’s creator, was awarded the Medal of Honor by the National Sculpture Society for his accomplishment.

But a group called SPIRIT (the Society to Protect Indigenous Rights and Treaties) has gathered community feedback about the Centennial Land Run Monument from Native Americans living in Oklahoma.

When asked how the current series of sculptures made them feel, one of the participants in SPIRIT’s survey responded, “It makes me feel like they are proud of what they did to my ancestors and that they’re glorifying it. Many people don’t realize what had to take place in order for the land run to happen. I feel sorry and sad. “

Another said, “It feels like a celebration of colonization, of the stealing of Indigenous land and disenfranchisement of our people, and like a whitewashing of history that overlooks how that land came to be open for white settlers.”

Last year, SPIRIT issued a report with recommendations for how Oklahoma could more appropriately tell the story of its founding and a more complete history of the land run.

Rather than demand that the monument be removed, however, at the heart of SPIRIT’s report is this insightful, balance-seeking recommendation from its authors, known as the Knowledge Keepers: “The Native consultants for this project felt it is crucial to tell the state’s origin story in all of its complexity, and the story must include the experiences of Indigenous people.”

They envision a process that would involve Indigenous historians, authors and artists collaborating on a new public monument that would add to the story already being told, not eliminate or replace it.

SPIRIT, in essence, is applying the “Counterspeech Doctrine” made famous by Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis in 1927 when he wrote, in defense of free speech for everyone, even speech that may seem untrue or detestable, “If there be time to expose through discussion, the falsehoods and fallacies, to avert the evil by the processes of education, the remedy to be applied is more speech, not enforced silence.”

Brandeis issued his pronouncement nearly a century ago, yet today we find ourselves at a moment in America when grappling with challenging features of our nation’s history, like early colonization, the mistreatment of indigenous people, our country’s founding, the institution of slavery, and the Civil War, is fraught, even more than usual, with bitterness and political polarization; and when extremists at both ends often seek “enforced silence” over “more speech.”

In 2015, after a self-declared White supremacist gunman, who had published pictures of himself with the Confederate flag on social media, murdered nine Black worshippers at the Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) launched the Whose Heritage project to identify and publicly catalog Confederate memorials across the South. They included 780 monuments, 103 public schools, 3 colleges, 80 counties and cities, 9 state holidays, and 10 military bases named for heroes of the Confederacy.

More than 100 of those symbols were removed, ended, or renamed over the next few years including, less than a month after the shootings and with bipartisan support led by Republican presidential contender Nikki Haley, the Confederate flag that till flew over the South Carolina State House.

Enough was enough, some communities decided, and certain symbols that had come to represent or perhaps even promote racism and violence had to go.

Then, after the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer on May 25, 2020, hundreds more Confederate monuments were taken down, as well as statues of America’s slave-holding “Founding Fathers,”like Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, sometimes by angry crowds of protestors unwilling to wait for formal, political processes and community agreement.

The protestors and their supporters were convinced that they were on the right side of history, by eliminating it.

Defenders of the monuments and their supporters were similarly convinced that they were on the right side of history, by preserving it.

Who was right?

More recently, the state of Florida, which has already banned teaching “Critical Race Theory” in schools and restricted public colleges and universities from spending money on diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives, became the first state in the country to allow its schools to show videos created by PragerU.

Despite its name, PragerU is not a university, but a company created specifically to promote conservative values. Alongside episodes denying global warming science, their videos include Leo & Layla Meet Christopher Columbus, in which the famous explorer asks, “Being taken as a slave is better than being killed, no? Before you judge, you must ask yourself, ‘What did the culture and society of the time treat as no big deal?'”

Understandably, a chorus of critics has responded that the move is simply a form of indoctrination in right-wing propaganda.

The state of Florida is on a clear and determined path to erase parts of American history that some find bothersome, while replacing them with history that others find ludicrous.

In Mistakes Were Made (But Not by Me) social psychologists Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson explore the ways in which people justify their actions and avoid taking responsibility for their mistakes, noting that, “History is written by the victors, but it’s victims who write the memoirs.”

Indeed, it is worth remembering that the history you know (or think you know) is almost certainly, to some degree, shaped by those who have achieved “victory” (in battle, in political influence, in wealth, or by some other measure), while stories about the very real lived experiences and perspectives of the “victims” (those who lost in battle, or achieved less influence, wealth, or other measures of success) may be marginalized or ignored completely.

When history makes headlines today, it is often because of the clash between these two perspectives.

Writing for Foreign Policy magazine, Michael Hirsch cautions:

“…If today’s so-called cancel culture eventually extends its way to presidents like Roosevelt and the Founding Fathers, new problems crop up. If you cancel out the good history with the bad—if you cancel out Thomas Jefferson—what kind of country are you left with? As John Charles Thomas, the first African American appointed to the Virginia Supreme Court, once remarked, “Although Jefferson was imperfect, he had a perfect idea.” Even Martin Luther King Jr. invoked Jefferson’s declaration of equal rights as a “sacred obligation” in in his 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech, calling it “a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir”—but which the country, to date, had “defaulted on” for Black Americans.”

Apart from “cancelling” the past, though, there is a more moderate middle ground that has been staked out by leaders across the political spectrum when it comes to what we do with problematic emblems of our history, regardless of who has a problem with them.

Former Republican President George W. Bush, speaking at the grand opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in 2016, observed, “A great nation does not hide its history, it faces its flaws and corrects them.”

Former Democratic President Barack Obama, in an essay titled “How to Make this Moment the Turning Point for Real Change,” published in June 2020 following the killing of George Floyd, urged, “I don’t believe that it’s a good idea for America to erase our history, but I think it is appropriate to reflect on our history. And the best way to do it is to build new monuments and new memorials that honor the incredible sacrifices that were made on behalf of freedom.”

While it may be tempting to ignore, erase, or replace history that, for one reason or another someone finds offensive, if we do, we run the risk of losing that history, forgetting it entirely, not learning from it and, perhaps, repeating it.

In a pluralistic democracy, with free speech as a bedrock principle, not only is there room for everyone’s story, good citizenry demands that each story be told, understood, and remembered, as the Oklahoma Knowledge Keepers of SPIRIT encouraged, “in all of its complexity.”