About ten years ago, before I began writing these “Running the Campus” blog posts, I started sending out “Weeklies,” emails to the campus and community that usually included something about what was happening at NECC that week, a perspective on a big issue facing higher education, and a short story about my young daughters, who were known back then as “Big Sis T and Little Sis Z.”

A few of those early “Weeklies” are still in the Archives of “Running the Campus.”

Well, “Big Sis T” and “Little Sis Z” are much older now.

Me, too, I suppose.

And like many parents my age (just scroll through the Facebook and Instagram posts of your fifty-ish-year-old friends over the past week or so) I have just returned, a little wistfully, from delivering my precious daughters out into the world, Big Sis T to Los Angeles to pursue her music career and Little Sis Z to the University of Massachusetts Amherst to study business.

My wife and I have officially become empty-nesters.

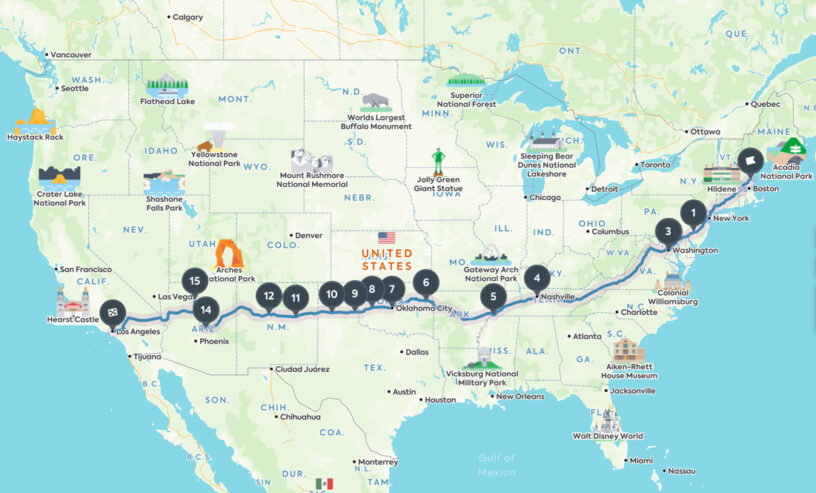

As a way of commemorating this important life passage, my daughters and I decided to road trip our way across the country, from Boston to Los Angeles, stopping along the way to take in some of the sights that make America unique (and a bit quirky).

Because I enjoy history and storytelling, and wanted to be ready to explain more about this nation of ours to Big Sis T and Little Sis Z as we trekked across it, I prepared for our adventure by reading a couple of famous travelogues: Stephen Ambrose’s Undaunted Courage, about Lewis and Clark’s 1803 voyage up the Missouri River, across the plains, and out to the Pacific Ocean; and John Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley in Search of America, about a journey the novelist took in 1960 when he was 58, just a few years older than I am now, to rediscover the Americans he had been writing about, but had not visited, in decades.

In many ways, the three journeys, Lewis and Clark’s, Steinbeck and Charley’s, and the Glenn Family’s, were far apart in time and quite different from each other.

Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery Expedition was a military and scientific venture, assigned to them by the President of the United States, Thomas Jefferson. The task of the 32-man corps was to navigate barges and canoes, ride horses, and walk along the inland waterways, across the plains, and over the mountains of the newly acquired Louisiana Purchase, mapping the western United States en route to the Pacific Ocean.

Over the course of their two-year journey, they hunted their own food, traded and established diplomatic relations with local Native American tribes, struggled through illnesses, injuries, and all manner of bad weather, and narrowly missed being intercepted and captured or killed by the Spanish army.

Steinbeck’s adventure was shorter and decidedly more comfortable, though not without its own mid-twentieth-century hazards. He and his French poodle, Charley, spent three months zig-zagging the country in a specially outfitted camping truck he named Rocinante, after Don Quixote’s horse. They drove from New England to the Midwest, then on to the Pacific Northwest, California, Texas, and across the South before heading home to Long Island.

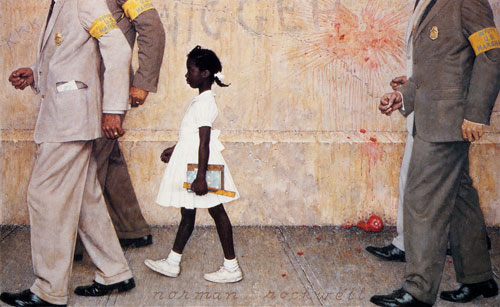

Along the way, they camped and occasionally stayed in motels, meeting colorful characters like a taciturn farmer in Maine; a smug short order cook and waitress in Minnesota; the son of an Idaho mountain man studying to be a hairdresser; and, in some of the book’s more troubling and revealing passages, a group of horrifically racist women in New Orleans, staging profane protests over the integration of black students into previously all-white public schools.

The trip that Big Sis T, Little Sis Z, and I took was even shorter, more luxurious, and far less perilous. In a week, we traveled 3,439 miles, from Boston to Washington, DC, then on to Nashville, Oklahoma City, Albuquerque, Flagstaff, and Los Angeles. Instead of canoes, horses, or an old camping truck, we drove a brand new, rented Chrysler Pacifica minivan with reclining seats and satellite radio, stuffed to the ceiling vents with Big Sis T’s musical instruments and belongings.

We grooved to our own “America Coast-to-Coast” playlist, and listened to podcasts about American history.

We caught a performance of Six, the musical about the wives of Henry VIII, at the National Theatre in DC; bought boots and danced to country music on the strip in Nashville; pilgrimaged to Gracelend and ate catfish on Beale Street in Memphis (thank you, Elvis and Marc Cohn); picked up and followed the iconic Route 66 across Oklahoma and the Texas panhandle; hooted at the World’s Oldest Continuous Rodeo in Payson, Arizona; and marveled at the Grand Canyon and Joshua Tree National Park before arriving at Santa Monica Pier, the end of the line, a couple of blocks from T’s new apartment.

We also visited some of the historical sites and roadside oddities that make trips like this memorable: The Liberty Bell in Philadelphia; Popeye’s Statue in Alma, Arkansas (the “Spinach Capital of the World”); the Route 66 Museum in Clinton, Oklahoma; the Cadillac Ranch near Amarillo, Texas; the deep, refreshing “Blue Hole of Santa Rosa” (scuba diving a thousand miles from the ocean—who knew?); and Gallup, New Mexico, “The Most Patriotic Small Town in America.”

As far apart in time and as different from each other as these three journeys were, in many ways they were also similar experiences.

Yes, the system of interstate highways and “fast food” restaurants sprouting up in the 1950s that Steinbeck bemoans as abominations on the landscape have only spread faster and farther since then, with local gas pumps and Howard Johnsons giving way to shiny Mobil stations and Subway Sandwich shops.

But most of America is still vast, open space, barely touched or changed since Merriwether Lewis and his dog, Seaman, crested the Continental Divide in Montana in 1805 and wrote in his journal, “We proceeded on to the top of the dividing ridge from which I discovered immense ranges of high mountains still to the West of us with their tops partially covered with snow.”

On our journeys, Lewis and Clark, Steinbeck and Charley, and Big Sis T, Little Sis and I all discovered that:

America is an enormous country, far bigger than we think about in our day-to-day lives, wherever we live them.

There is great beauty in every region of the country, and each of those regions, has its own distinct culture, shaped by geography, topography, climate, and hundreds of years of human history and experiences.

In addition to having its own distinct culture, each region also shares in our national character.

As Steinbeck observed more than half a century ago, and as any one of us might note again today, despite what often feels like an age of rising national discord, “For all of our enormous geographic range, for all of our sectionalism, for all of our interwoven breeds drawn from every part of the ethnic world, we are a nation, a new breed. Americans are much more American than they are Northerners, Southerners, Westerners, or Easterners.”

Summing up his experience on the road, Steinbeck also wisely wrote that, “People don’t take trips—trips take people.”

By which he meant that travelers may plan all they like, and must still be ready to adapt to the world they discover along the way; and that the best trips leave indelible impressions on travelers, shaping them, like the landscapes through which they journeyed, for years to come.

As Big Sis T and Little Sis Z, and those of us back at home, embark on this next great adventure in our lives, may we all adapt happily to the worlds we discover along the way, indelibly shaped by our travels together…